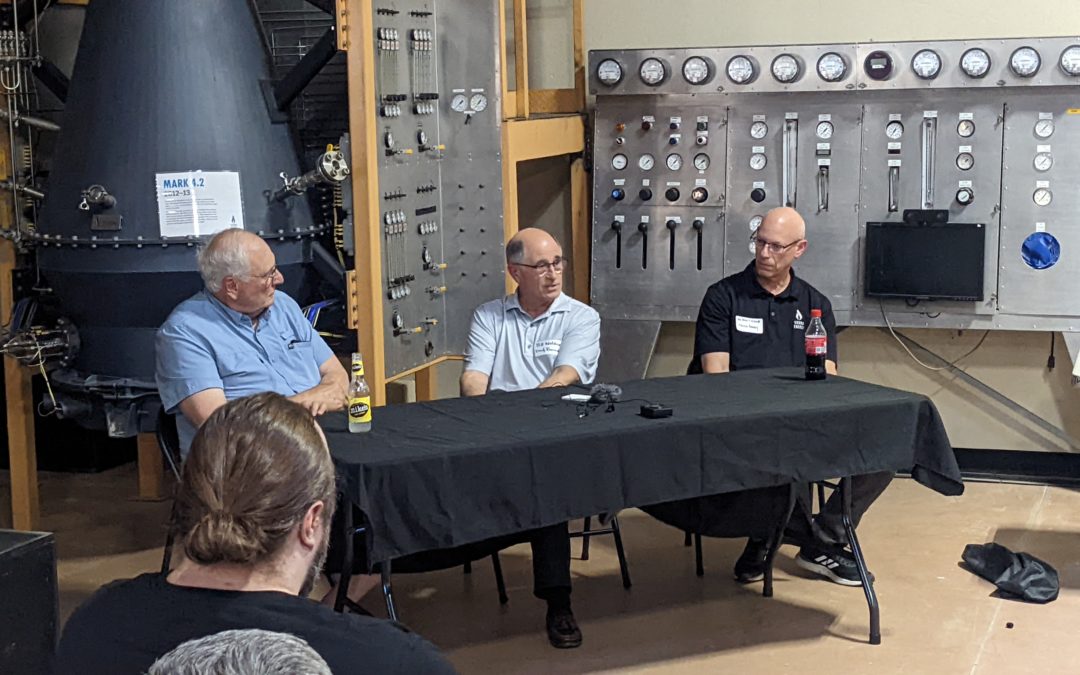

On June 2, we gathered for our second post-pandemic in-person MeetUp in Davis to hear from two companies that have spent two decades in innovating systems to convert wastes to energy products profitably.

First up, Michael Kleist, VP of Business Development, took us through the latest status of Sierra Energy’s FastOx waste gasifier development. Sierra has been developing this process for two decades. They achieved a major milestone in building a test facility at the 165,000-acre Fort Hunter Liggett in Monterey County and commissioning it in 2019. It is now processing 10 tons of waste per day. Sierra is using this plant to do test runs of various wastes in order to learn what it needs to improve or adapt to handle this variation. The plan is to perfect a design for a 100-ton per day commercial unit. Sierra got an investment from Breakthrough Energy Ventures to make the completion and operation of this unit possible. It is now seeking another investment round to move up to offer the larger plant. The FastOx process is a high temperature destruction of wastes using pure oxygen to avoid complications of using air (which is 80% nitrogen) and to provide the high temperatures it requires. The offtake streams demonstrated on the plant include a hydrogen rich synthesis gas (that can be made into methane, methanol, or even gasoline and diesel), purified hydrogen, and non-leachable solidified slag and stone (nothing that would be toxic). No ash would be produced. Other advantages of FastOx are its avoidance of moving parts, using an updraft fixed bed, control of tar formation, a very high yield of synthesis gas, and ability to run on heterogeneous post-recycle mixed waste and even RDF.

Next, Bill Walden of Trinity Renewable Technologies explained its new anaerobic digestion process. In contrast to the thermochemical approach of FastOx, the Trinity process occurs at much lower temperatures and relies on biological processes. The goal for Trinity was to be able to convert the material in organic waste that has the highest energy potential—the lignicellulose. Most anaerobic processes cannot deal with the lignin fraction, and convert only the cellulose. Trinity obtains rights to use an extremely thermophilic microbe discovered in Russia that breaks down the lignin very efficiently. The Trinity system actually uses to reaction vessels, one operating at high temperature for the pretreatment of the lignicellulose, then a more conventional digester that operates at a more moderate temperature and uses an “induced bed reactor.” (Although Bill did not reveal the exact temps, my guess is that “high” means 190-210°F, and “moderate” means 130-150°F which is common in digesters.) The result is the near complete destruction of all the solids in the waste, very unusual for a digester system. The products of the digestion are methane with a few other sulfur-rich gases, carbon dioxide, and an inorganic nutrient-rich irrigation water.

The target customer for Trinity is a dairy which typically digests only the wash water coming out of the milking barns to generate methane. The leftover manure is usually just stacked up and left to compost, unfortunately releasing fugitive methane. The value of the Trinity system is that it can increase the captured methane yield by a factor of 2-4, according to Bill. He said they are close to some deals for building systems in the dairylands of Wisconsin.

In the discussion which followed, we talked about the impact of low-carbon fuel rules on the market prices for products of these two very different processes. (We had a discussion specifically on these rules last September and you can look there for a better understanding of them.) Unfortunately, the existing rules and calculation methods under the Low Carbon Fuel Standard in California do not yield a very good result for FastOx. The gas produced is not considered to have a relatively low Carbon Intensity Score, even though there clearly is a fraction in the waste of organic material that should be treated favorably. Sierra’s response has been to focus on customers who do not care about the California score—customers overseas or customers who simply want to avoid landfilling their waste. Sierra has found so many potential customers of this type that it sees a bright future for its upcoming 100 ton per day commercial system.

Trinity has been hit with another quirk in the California system which ends up penalizing dairies for producing methane from the unconverted solid waste fractions, which seems upside down from what was intended. In all likelihood, the Trinity system will be most attractive if the output can be sold with a substantial California credit. That credit system applies, even if the methane produced is far from the borders of California. Bill mentioned effort underway to correct the calculation method through legislation to remove the “quirk” that penalizes anyone trying to do a better job of methane capture at dairies.

From this discussion it seems some fresh ideas on dealing with wastes are about to bear fruit. It’s only taken two decades.

Be sure to join us for a future monthly MeetUp in the evening and keep an eye on the upcoming schedule for our Perspectives podcast held several times per month in the morning.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gary Simon is the Chair of CleanStart’s Board. A seasoned energy executive and entrepreneur with 45 years of experience in business, government, and non-profits.

CleanStart Sponsors

Weintraub | Tobin, BlueTech Valley, Revrnt,

Moss Adams, PowerSoft.biz, Greenberg Traurig